Why MaaS Will Keep The Car In The City

by Peter Lakin, President of acompani

In the late 19th century, the horse was the King of the Road.

In Paris alone, there were over 80 000 of them being used for personal transport, for deliveries and for services. They were fuelled on biomass and water and their emissions were recycled for use in agriculture.

They were the ultimate in Green Mobility!

Except that…

…their emissions amounted to over 1 200 tons of excrement per day, which created some other externalities for the city residents. Green was not necessarily clean.

When the automobile became available in the early 1900s, it replaced 95% of the horses within a period of about 20 years and contributed significantly to the cleanliness of the city.

Now this fossil fuelled means of transport is itself under attack for its negative impact on the environment.

There are two lessons from this story:

- there are pros and cons to every solution

- the optimal solution depends on the problem that we are trying to solve

So what is the optimal solution for urban mobility and can it be achieved at an acceptable economic and human cost?

Contrary to some visionary optimists, I take a more pragmatic view of the benefits (and the costs) of new technologies. I believe that there is no silver bullet and that in the foreseeable future, there will need to be a combination of solutions to meet the real needs of real people.

As in my last article, I will take Paris as an example because it is one of the most innovative cities for transport in the world and it is also close to home.

What is the problem that we are trying to solve?

“The main issues for transport in the city are Safety, Air Quality, Congestion and Accessibility” says Anne-Marie IDRAC, speaking at a recent INSEAD conference on Urban Mobility. She is a former French Government Transport Minister and she recently published the Strategy for the Development of Autonomous Vehicles in France.

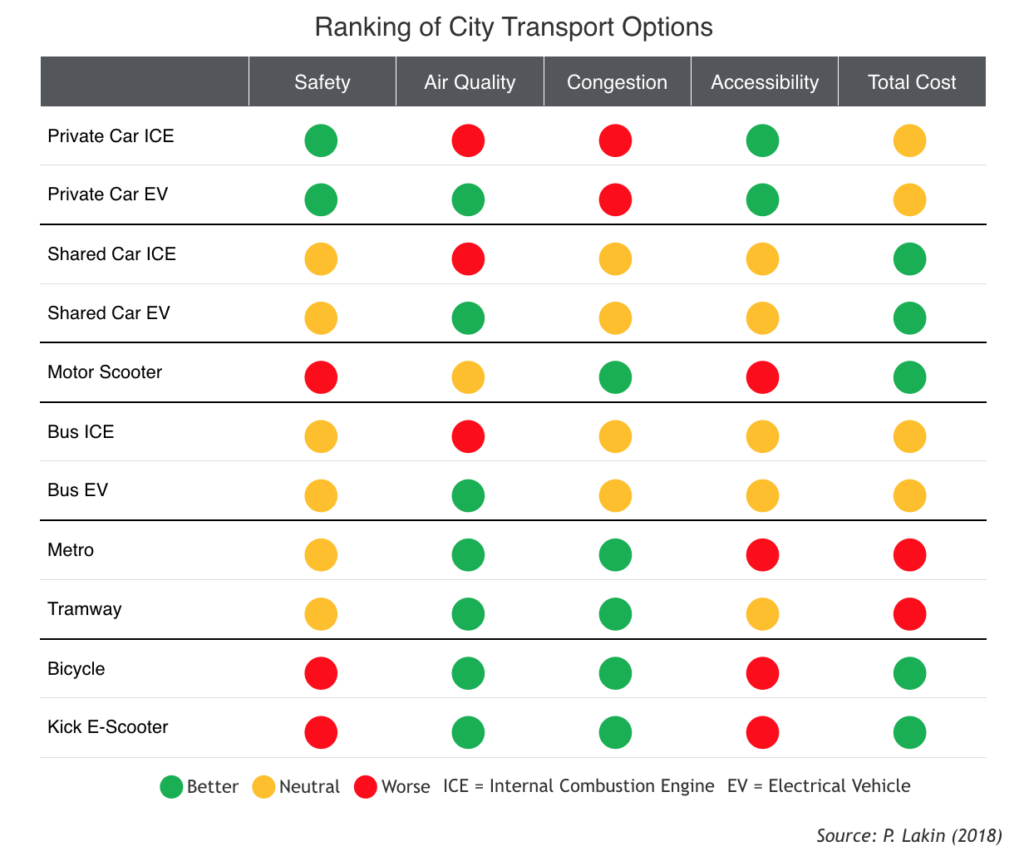

This is a helpful list to use to compare the different options for city transport but we should also add Total Cost, including both initial investments and running costs, as any solution needs to be affordable.

My simplified comparison is shown in the table below.

As expected from earlier comments, there is no single option which is best on all criteria.

Some of the rankings may look surprising and can certainly be debated, so let’s start the debate with my side of the argument.

Safety

There were 31 road deaths in Paris in 2017 according to the ONISR, a rate of 17 per million people, which is significantly lower than the overall rate in France of 53 road deaths per million people. Two thirds of the Paris deaths were pedestrians, cyclists or motorcyclists, not car drivers.

The majority of accidents in France involving cars alone occurred outside the city, which helps to explain why the Macron government recently reduced the speed limit on rural roads from 90km/h to 80km/h.

Two wheeler riders are more at risk from death or serious injury if involved in an accident. Outside the city, many of these accidents are caused by collisions with cars but inside the city, it is more likely to be collisions with trucks or buses. According to RoSPA, heavy goods vehicles accounted for over 70% of cyclist fatalities in London in the last three years.

Data from Amsterdam showed that the number of cyclist deaths involving motor vehicles has declined and currently 40% of cyclist deaths do not involve motor vehicles. The introduction of the electric bicycle has seen increased usage by older people, which unfortunately has translated into an increase in cyclist deaths for the over-65s.

But safety should not be measured by road deaths alone.

On public transport, there was at least one serious incident every day on the Paris metro in 2017 according to RATP. Although many of these were suicides, there were also 280 reported falls between the platform and the train, which has now obliged RATP to launch a specific communications plan to warn passengers of this danger.

Passenger agression has been a problem on some trains and buses and this has deterred more vulnerable people from using public transport in the late evening. There have even been reports of some metro drivers refusing to stop at stations which suffer from drug related crime.

This has driven some potential metro passengers to use ride hailing apps. Unfortunately even here there have recently been reports in the local press of agression against women in taxis at night

It’s not surprising that from the driver’s or passenger’s perspectives, the private car is still seen as one of the safest options for travel in the city.

Air Quality

Any vehicle with an internal combustion engine (ICE) emits higher pollutant levels from its drive train than a purely electric vehicle (EV). This penalises all ICE cars, taxis, buses and motor scooters. Even hybrid vehicles are concerned as they have both ICE and EV capability.

In general, the larger the ICE vehicle, the higher the level of pollution, which makes trucks and buses particularly bad. Hence the drive to encourage the use of electric vehicles or more efficient exhaust after-treatment systems.

Paris already has a scheme in place to limit the number of ICE vehicles entering the city, based on the level of exhaust after-treatment that is fitted. The Crit’Air labels differentiate between older, higher polluting vehicles and modern, lower polluting vehicles. It is used on days when air pollution is particularly bad.

But air quality should not be measured by exhaust emissions alone.

Although all the EVs are shown in green in the table, more work needs to be done on the non-drive train pollution from vehicles. For example, brakes and tyres are a major source of particulate pollution and the heavier the vehicle, the higher the amount of particulates. Unfortunately, EVs tend to be heavier than ICE vehicles due to the weight of their batteries.

Particulates from brakes are also a problem in the metro, where measurements made by Airparif inside some metro stations exceed the legal limit outside the station by a factor of 3 or more.

After the anti-Diesel lobby, will this be the next target for the city of Paris?

Congestion

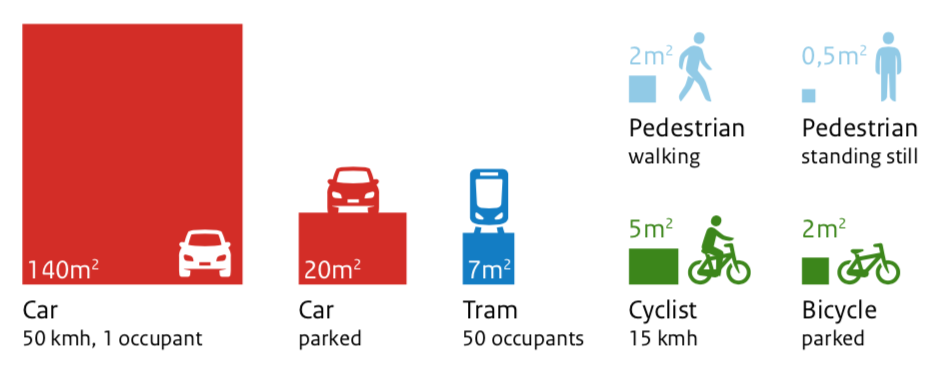

The road space taken up by each vehicle per passenger is probably the best way to assess congestion.

Source: Netherlands Institute for Transport Policy Analysis Single occupancy cars are clearly the worst for congestion, which is why car sharing is seen as a way to improve the situation. However, even with a full car of 5 people, the road space used would still be 4 times greater than for a busy tram and over 5 times greater than a cyclist.

Interestingly, as most taxi journeys are for only one passenger, the taxi is one of the least optimal solutions to congestion, despite the use of dedicated taxi lanes.

“To solve congestion, we can either redesign the city or we will need regulation” according to Xavier MOSQUET, Senior Partner at BCG, and currently working for President Macron on Automotive and Mobility.

At a recent conference organised by the Mairie of Paris, the city of Pontevedra in Spain was used as an example of how regulation can work. Cars are banned from the city centre unless strictly necessary and drivers need to park their cars on the outskirts of the city and then walk or cycle to their destination. The city proudly says that one can walk across it in 25 minutes.

However Pontevedra has a surface area of only 4,5 km2 for 83 000 people compared to 105km2 for 2,2 million people in Paris and walking across the city in 25 minutes is not an option in Paris.

A better comparison would be with the four central arrondissements in Paris, which have an area of 5,6km2 and a population of about 100 000.

Could this area be fully pedestrianised?

Unlike Pontevedra, there are no free car parks on the outskirts of this area, where drivers can leave their cars and in any case, this would not help congestion elsewhere in the city.

Clearly, reducing congestion will require fewer cars, vans and trucks in the city.

Some form of regulation to limit the number of vehicles entering the city seems necessary but introducing a congestion charge like in London would be politically difficult in Paris, especially after the recent yellow vest demonstrations in France.

However if regulation is combined with actions to help drivers to park outside the city and with incentives to encourage the use of walking, cycling, scooters and public transport, maybe it could work.

Accessibility

With an ageing population, Paris is typical of many cities in the developed world. Even in cycle friendly cities like Amsterdam and Copenhagen, it has been shown that older people are less likely to cycle or to use kick scooters.

A recent survey in Paris found that public transport, especially the metro, poses serious problems for push chairs and wheel chairs, especially in rush hours.

The car is still seen as the best solution for overall accessibility and the private car, which enables point to point pick up and delivery, is seen as a better solution than a shared car, which may have to be met at a specific point in the street.

Much work is going on to improve access to public transport for older and disabled people but it will take time and further investment.

Taxpayers would be justified in asking if this is the best use of their money or if it would be economically more efficient to encourage forms of private transportation for this segment of the population.

Total Cost

Like all public services, public transport costs need to be paid by the users or by the tax payers.

For the user, the cost of an all-zone monthly public transport pass in Paris is 75 Euro, which is about a third of the cost of a 5-zone monthly pass in London, so public transport seems to be good value in Paris.

However this is because it is subsidised to the tune of 70% by French tax payers and businesses.

So the true cost of public transport is not obvious at first sight.

Work by Jean Coldefy suggests that the net cost to the local government of subsidising public transport in a mid-size city like Lyon, is 160M Euro/year versus only 20M Euro/year to maintain the road network for cars.

Neither of these costs include the depreciation of the initial investments in infrastructure, cars, buses or rolling stock, which would most likely make the relative cost of public transport even higher versus the car.

Cities which do not already have an extensive public transport system and which are looking at how to improve mobility, do not always agree that investing in new public transport is the best use of tax payers’ money.

According to The Economist newspaper, voters in Nashville recently rejected a plan to build tram and rapid bus lines as they believe that autonomous cars and buses would soon be a cheaper and better way of transporting people.

Clearly the lowest cost options are e-scooters and bicycles. Estimates of the business model of private e-scooter leasing companies suggest that the initial investment of about 400 Euros has a payback of less than a month when earning 20 euros per day.

Electric bicycles at about 1 500 euros each, have a longer payback period.

Car sharing initial investments of between 20 000 and 30 000 euros each, require even longer payback periods but compared to investing in a new tramway, the economic equation is much more attractive.

And the winner is…

So where does this leave us regarding the best option for transport in the city of Paris?

For a young, able bodied person who wants to go directly from one point in the city to another, a combination of the metro and an e-scooter or bicycle would seem the perfect choice.

For an older person or a young mother with a baby who wants to go shopping, a bus or tram at street level would seem the best public transport option, provided that the journey was made outside the rush hour and that the weather was fine.

But for those who can afford it, the easiest option is clearly the private car or a taxi/shared car.

For a business visitor who does not know the city or the language well, the most common solution is a taxi or a ride hailing app, like Uber. Public transport may be cheaper but when the fare can be charged to expenses, the car is much more convenient.

For someone who lives outside the city and travels in to work, a combination of a car to the local station then a train into the city, followed by a metro or bus to the final destination is the classic commute.

Although there are several options to get from home to the local train station, the private car is often the vehicle of choice, especially when it is possible to park for free at the station.

“Public transport works well in built up areas but less well in rural zones” says Xavier MOSQUET.

Because of this, it is hard to see out of town commuters giving up their cars in the short term.

And if they have their cars, then they will want to be able to use them to drive into the city at times when public transport is either too infrequent (at weekends) or too dangerous (at night).

So cities need to be prepared for the fact that cars will continue to be part of the solution and they need to find a way to integrate them into future mobility planning.

MaaS to the rescue?

The title of this article is Horses for Courses because its argues that the best transport option depends on the each person’s specific circumstances; their age and gender, their destination and reason for travelling, the time and distance of travel, their budget, etc.

There is no one solution that meets everyone’s needs and that is why the best solution will be a combination of transport options.

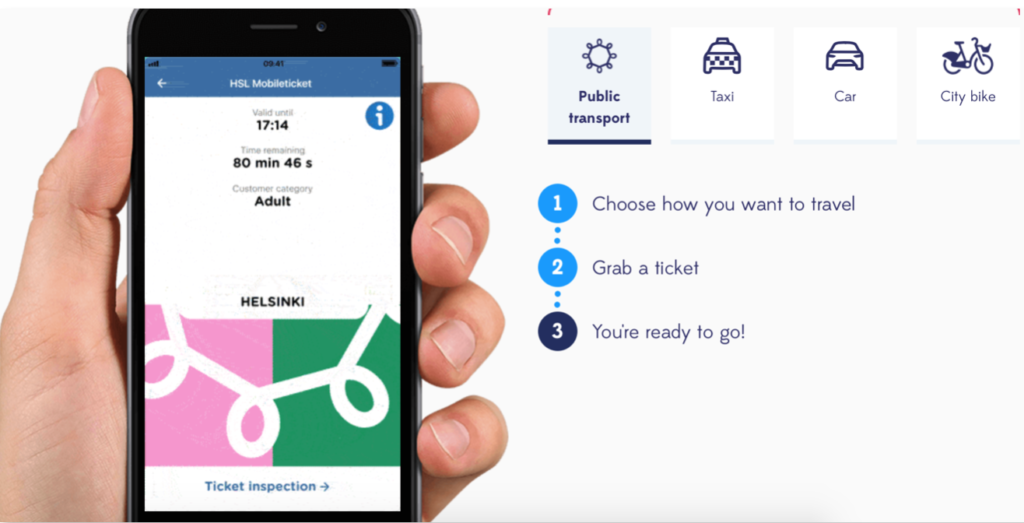

This is the logic behind Mobility as a Service, often abbreviated to MaaS.

MaaS is a bundling of mobility services through one app and one payment channel. It allows a traveller to switch between a car and a train or bus, then to an electric scooter, bicycle or kick scooter. There is no need to buy several tickets and a well managed app can ensure that there is no waiting between changes of transport options.

It is the new battleground for many start-up companies and city transport authorities.

Helsinki is home to the Whim app, which started in 2016 and currently manages 60 000 trips by their 7 000 subscribers each month. Most subscribers pay a 49 Euro monthly fee that gives them access to unlimited public transport and reduced rates for taxis.

Uber is also very active in this area and recently joined the MaaS Alliance, a public-private partnership based in Brussels, that seeks to facilitate a single, open market and full deployment of MaaS services in Europe. Uber’s strategy has evolved from its initial offer of luxury private transport to its current goal “to democratise mobility”.

However both Uber and Whim will have to find a way to cooperate with existing city transport authorities, who are understandably reluctant to hand over full responsibility for transport management in their cities to private companies.

For example, two years after its launch, Whim was still fighting with the Helsinki public transportation authority to get access to its monthly pass option.

The high valuations of companies like Uber and Whim will depend on how successful they will be in cooperating with cities for MaaS, so it’s worth watching developments closely.

Whoever comes out on top, the good news for passengers is that MaaS looks like it will become the future of urban mobility.

The good news for car makers, is that cars will continue to be part of the mix, although they will need to be zero emissions in the future and perhaps also autonomous.

Oh yes, the autonomous car!

It’s a big topic and it deserves an article all to itself, which is coming soon…..

I like the helpful information you provide in your articles.

I’ll bookmark your blog and check again here frequently.

I am quite certain I’ll learn many new stuff right here! Good luck for the next!

This site really has all the information and facts I wanted concerning this subject

and didn’t know who to ask.