by Peter Lakin, President of acompani

After much debate, climate change is now accepted as a reality. However since the COP21 in Paris in 2015, the momentum across the world to take measures to limit the rise in global temperatures to 1,5°C has been dissipated and progress has been slow. This has given rise to “people power” with school strikes and demonstrations in the streets by organisations like Extinction Rebellion. Whether the governments agree or not, the people see climate change as a real threat.

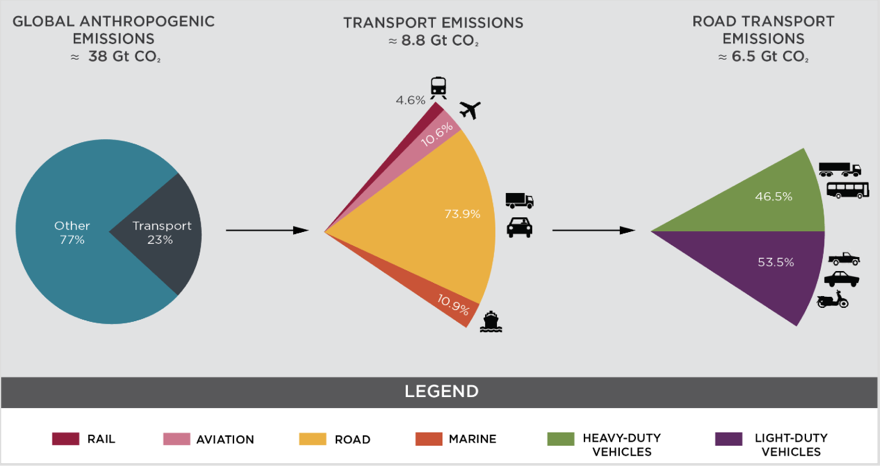

Several studies have estimated that the transport sector currently contributes around 23% of man made CO2 emissions and the OECD has estimated that transport’s contribution could rise to 40% by 2030. Road transport is seen as being the main source of CO2 and this has led governments to introduce fiscal measures to tax road transport, ahead of other sources of man made CO2.

In parallel to the concerns about climate change and CO2 emissions, road transport has also been blamed for the increase in poor air quality across the world.

The World Health Organization estimates that over 80% of urban residents are exposed to air quality levels that exceed their recommended limits. This has led to the creation of Low Emissions Zones, Clean Air Days and other measures to reduce the number of cars and trucks on the road.

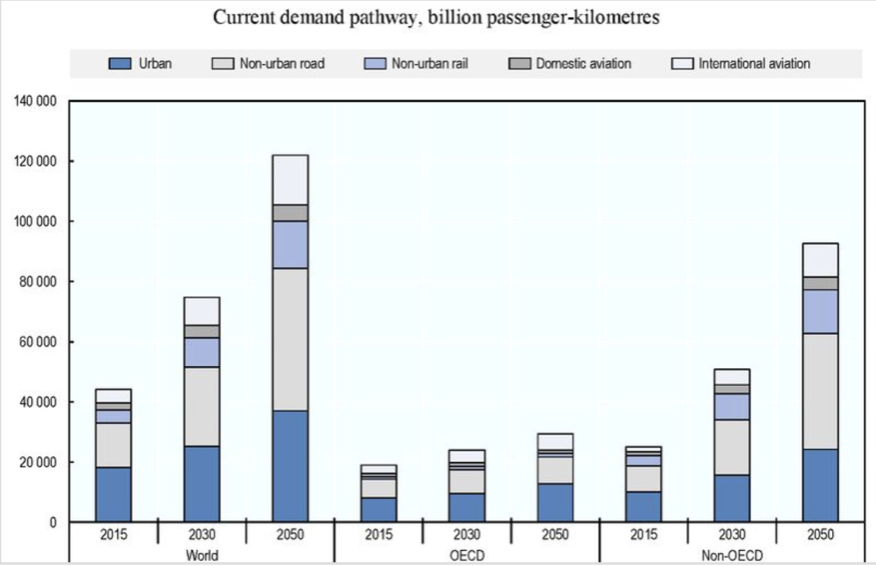

Unfortunately for the climate and for urban air quality, the need for both passenger transport and freight is increasing each year.

According to the OECD, the growth in passenger transport worldwide is forecast to increase by a factor of 3 from 2015 to 2050, with the highest increase coming from China and India.

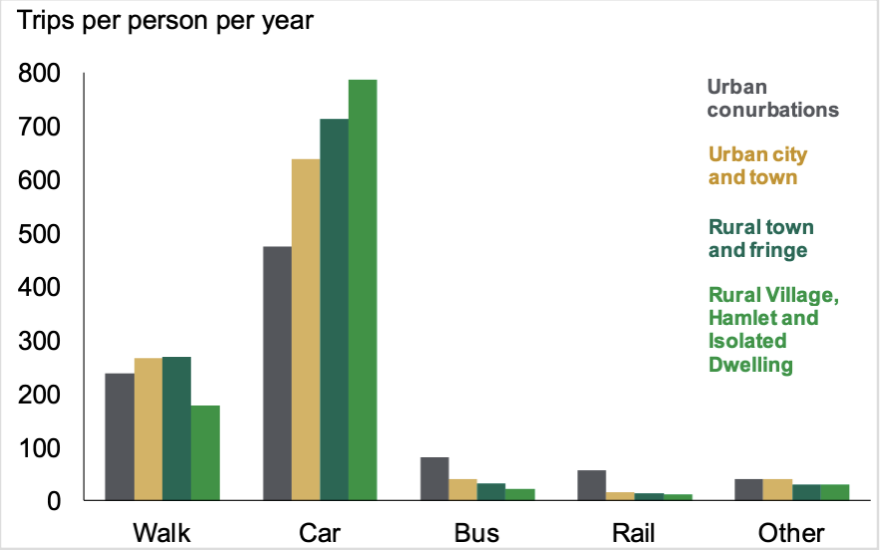

Although there has been an explosion of start-ups proposing bicycles, scooters and ride hailing in many cities, these often do not address the travel needs of people living outside city centres.

Research carried out in England in 2017 by the Department for Transport, showed that the car is by far the preferred form of transport for people living in rural and semi-rural areas, where public transport is less available than in a city.

Given that there is likely to be a continued demand for passenger cars in the future, the focus of many local and national governments is now on reducing emissions from these vehicles, both toxic pollutants and CO2.

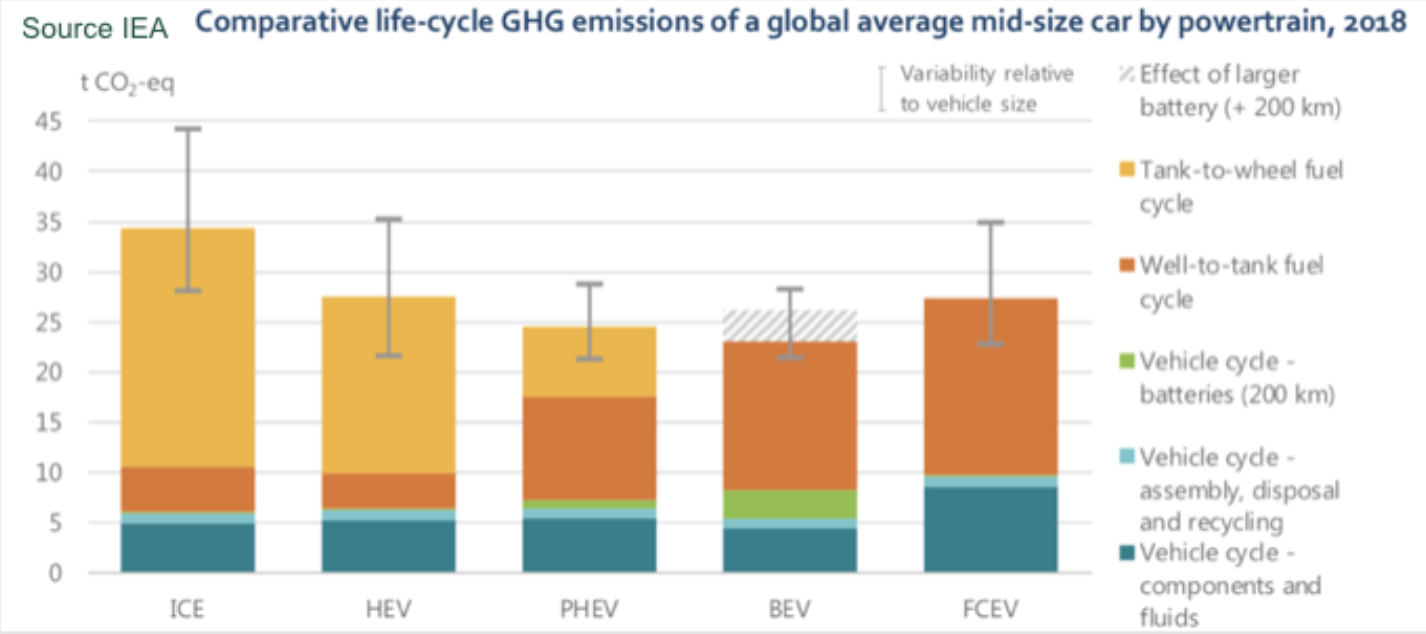

The solution that many are promoting is the Electric Vehicle. This will reduce tailpipe emissions to zero but the impact on CO2, from generating the electricity and from manufacturing the batteries has been questioned.

Let’s look first at the CO2 generated from driving. For every 100km, a mid-size gasoline car uses about 7 litres of gasoline, which accounts for about 16kg of CO2. A similar size electric car uses about 19 kWh of electricity which accounts for between 7 and 10kg CO2, depending on the source of the electricity. If we use the European average of 350gCO2/kWh or the World average of 520gCO2/kWh for generating the electricity, the electric car offers an advantage of 6 to 9kg CO2 for every 100km.

Clearly in countries where most electricity is generated from low CO2 sources like hydro, wind, solar or even nuclear, the CO2/kWh is much lower, which increases the advantage of the electric car.

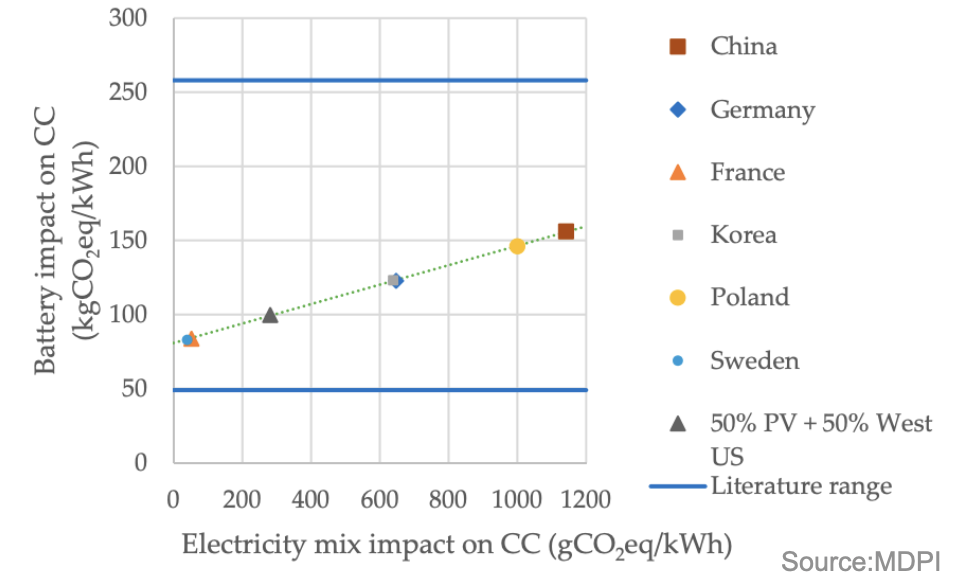

Let’s now look at the energy required to manufacture the batteries. The CO2 emissions again depend on the source of the electricity needed in the manufacturing process and it ranges from less than 90kg/kWh in Sweden to over 150kg/kWh in China. So a 50kWh battery would account for between 4500 and 7500kg of CO2.

Ideally, all batteries would be made in countries where electricity is generated from low CO2 sources. Unfortunately, today most batteries come from countries like China, where CO2 emissions from generating electricity are particularly high due to a dependence on coal fired power stations.

Based on these calculations, an electric car would need to drive over 50 000km before its CO2 emissions would be less than a gasoline car.

As the actual lifetime distance of a car is closer to 200 000km, even today the CO2 balance of an electric car is favourable. Given the progress on renewable energies, (Tesla has said that its Gigafactories will be entirely powered by renewable energy sources) this advantage will become more favourable in the future.

Based on this type of analysis, governments have been promoting a switch to electric and there are a number of cities and countries, which have announced bans on the sale of new gasoline and diesel cars in the future. There is huge regulatory pressure in Europe and in China to transition to electric.

This year 2020, European legislation requires the average CO2 emissions of all new cars sold to be no higher than 95g/km when measured on the test cycle. There will be significant financial penalties for car manufacturers who exceed this limit, after adjustment for the average mass of their new car sales fleet.

Initially, car manufacturers thought that they could meet this limit by selling a large share of diesel cars but since the Dieselgate scandal, the share of diesel has declined severely. Therefore to compensate, the car manufacturers will be obliged to increase the share of electric and hybrid cars in their sales. Hybrid cars will still need an Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) but what will happen with pure electric cars, that do not need an ICE?

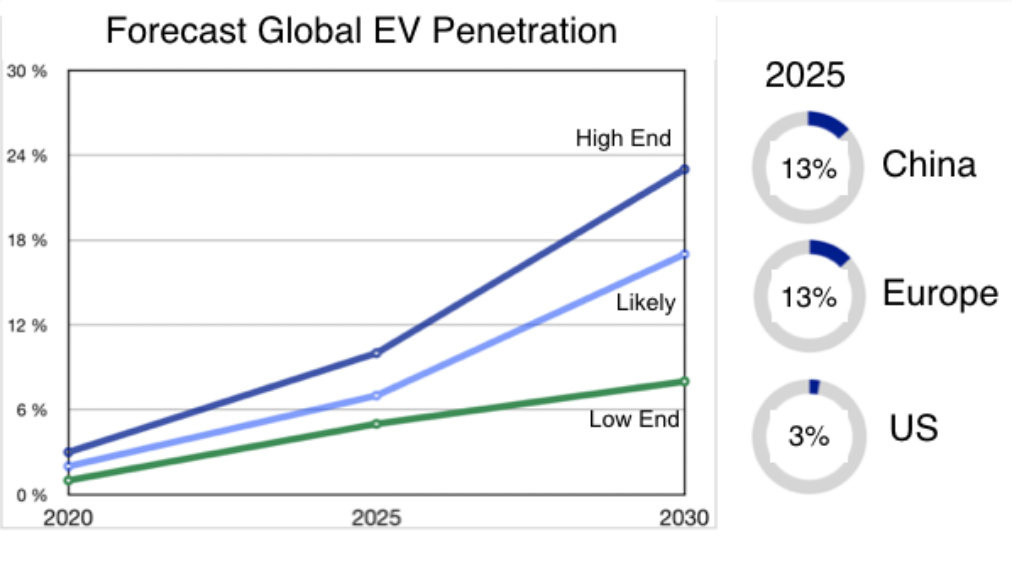

It has been estimated that after 2020, full electric cars (no ICE) will need to make up between 7% and 10% of European new car sales in order for car makers to meet the CO2 regulations.

Post 2025, when the legislation will require average CO2 emissions to be no higher than 81g/km, this share could be between 16% and 25%.

In the face of this push to electric in Europe, there will be a huge number of new electric cars introduced to the market.

The question is will consumers buy them?

There are several factors which could limit sales of electric cars, including:

Battery Availability

Vehicle Cost

Range Anxiety

The main component of Vehicle Cost is the cost of the battery.

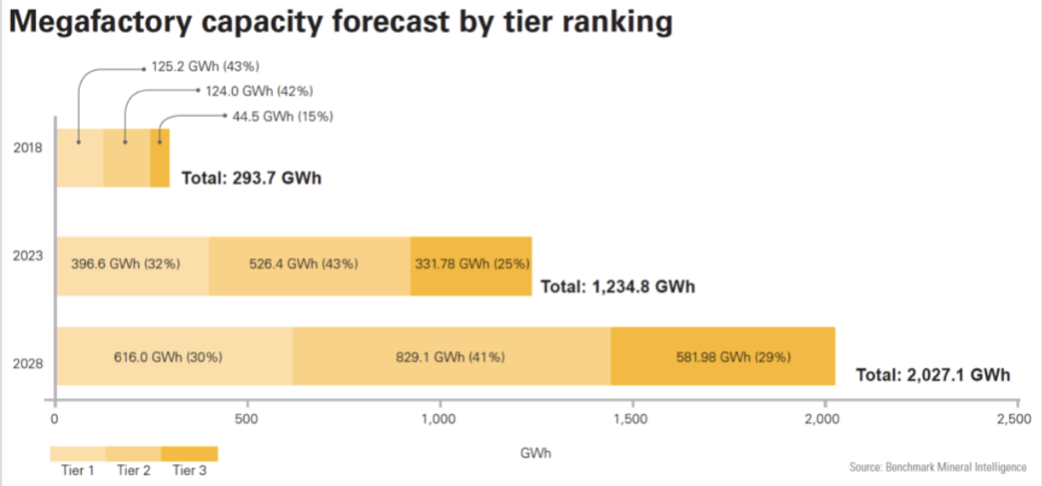

Global battery production for EVs is forecast to increase from under 300 GWh to over 1200 GWh by 2023 and to over 2000 GWh by 2028.

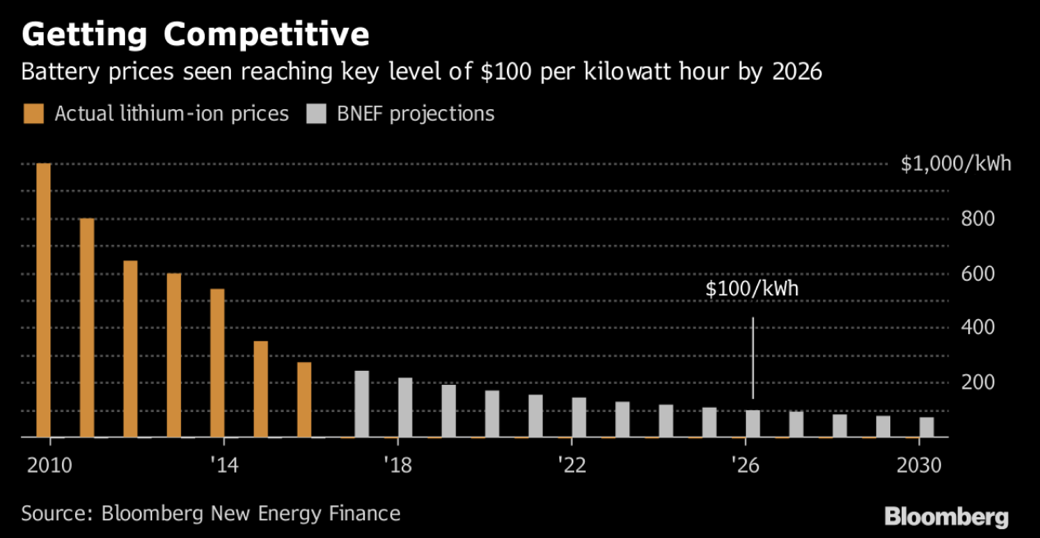

At the same time, this increase in scale and advances in technology, are forecast to bring the cost per kWh down from nearly $300 today to under $100 by 2026.

Given that electric cars are currently estimated to cost about $12 000 more than a gasoline equivalent, this will remove most of the cost penalty and make them as affordable as an ICE equipped car.

Because today, cost is a big issue. It’s why, the highest share of electric cars to total new car sales is localised in a few countries in Europe, notably Scandinavia, Netherlands, Switzerland and Belgium. In the US, California accounts for 12% of the US population but 50% of electric car sales. Inside California, Silicon Valley, which accounts for only 2% of the US population buys 20% of the country’s electric cars. There is a clear link to affordability as measured by GDP per capita.

Another factor holding back massive adoption of electric cars is Range Anxiety. Despite promises that new electric cars will have an autonomy approaching that of their ICE equivalents, there are still too many stories going around of drivers being stranded with flat batteries or having to pay premium prices for last minute recharging.

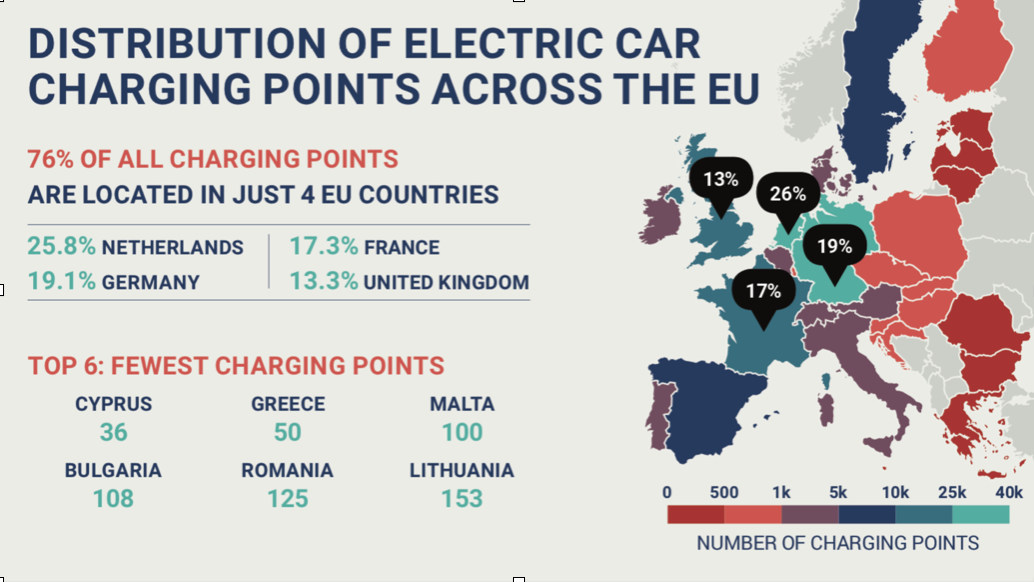

In order to combat this range anxiety, countries are investing in increasing the number of public charging points. However today the distribution of these charging points is concentrated in a few countries in Europe and is even more localised in the US and China.

In conclusion, I would say that climate change and air quality pressures are definitely creating a transition towards electric cars. However at a global level, this transition will take some time. It will be limited by:

- costs of new electric cars versus ICE equivalents (especially in demand SUVs)

- roll out of the charging network to combat range anxiety

- profitability of car manufacturers (car makers will try to sell the minimum required by law in order to maximise returns on existing investments)

In fact the decline of new car sales with an ICE (including hybrid cars), will most likely not happen before 2030 and it will be relatively slow even after this date.

I estimate that ICEs will still be needed for over 80% of passenger cars worldwide in 2030.

ICE share will be lower in China and Europe because of the regulatory pressure but North America and the Rest of the World will continue to base their road transport systems around ICE technology.

For freight deliveries and many other commercial vehicles, the share of ICE engines will be even higher, with the vast majority still using diesel technology. In the future, perhaps Hydrogen Fuel Cells will enable large trucks to go electric but currently the weight of batteries required to travel long distances reduces the payload of the truck, which directly impacts the truck operators profitability.

So, with the overall demand for passenger transport and freight continuing to increase, the world could need another 1,3 billion Internal Combustion Engines from now to 2030!

Like!! I blog quite often and I genuinely thank you for your information. The article has truly peaked my interest.

I discovered your weblog website on google and check a few of your early posts. Continue to maintain up the superb operate. I simply further up your RSS feed to my MSN News Reader. Seeking ahead to reading more from you later on!?

Once I originally commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is added I get four emails with the identical comment. Is there any way you can take away me from that service? Thanks!